DeFi is bringing new excitement to the old idea of cooperative ownership. Customers get tokens, earn fees, and vote on decisions. In theory, this improves governance. In practice it accelerates customer commitment and adoption with a great loyalty reward. Can we apply this idea to the world of fund management?

It’s a $5T question. Private market investment through long-term limited partnerships has been massively successful. These partnerships fund much-needed innovation and infrastructure. They have delivered high returns for professional private market investors. LP funds now contain more than $5T worth of assets.

So, why mess with a good thing? There are a couple of reasons. For example, we might want to expand access by adding an easier way to resell investment stakes. Private funds require investors to lock up capital for ten years or more. This limits the number of investors that can participate, and creates a backlog of demand to buy in or sell out. This type of secondary trading has doubled over the past three years.

Coop funds have a different goal — to increase returns. We can increase returns by increasing the speed of fundraising, lowering the cost, and supporting innovation in fund formation.

Faster formation will allow funds to get into hot new categories while they still offer excess returns. It will also lower fundraising cost, which directly increases the returns available to investors.

A Rocky Start

Two years ago I shared my research on The Promise and Peril of Tokenized Funds. What happened next was not good. I covered the first wave of crypto-inspired funds with headlines like “How to make an awful tokenized fund that nobody will buy.” The first wave of offers included simple mistakes like not giving investors any way to get money back. Thankfully, they didn’t sell.

These early offers included more interesting mistakes, such as “bonuses.” A bonus is an extra share of the fund that gets paid to early investors. The theory was that these early investors are taking a risk, and they should get paid extra for the risk. In practice, this just took shares from later investors, and made the fund impossible to sell. Where early investors might get $1.20 in NAV for every dollar they put in, later investors might get $0.80. Nobody is going to pay a dollar for 80 cents. And, the risk analysis was fundamentally wrong. Early investors are not de-risking the fund when they expand it. They might make higher returns from a smaller fund. They are de-risking the fund MANAGER. If they deserve bonus shares, the shares should come from the manager.

Doing It Right

In a coop fund, early fund investors earn equity shares in the fund manager. As the fund gathers more commitments, later investors earn fewer manager operating shares, while earning the full returns from a fund supported by a growing community.

This can create a dynamic where a good fund offer quickly snowballs.

- Early investors can lower the risk of taking a chance on new fund managers and new types of funds. They get a meaningful voice in governing the fund, which helps them manage that risk.

- Investors have an incentive to commit quickly in order to earn bigger equity rewards. Then, they have an incentive to promote a fund where they are part owners.

Higher returns

This snowball can save time and money. Even successful new fund managers typically need about 18 months to find enough investors to get their fund started. That’s expensive in money, which they take out of the eventual investor returns. More importantly, it’s expensive in time. They start a fund in order to invest in a new opportunity with high returns, and fast investors will get those high returns.

Big, established fund companies don’t need this dynamic. They can raise new funds from their existing investors. In 2020, investors are funneling central bank liquidity and want to place money in large chunks. Big funds are getting most of the new investment dollars. Big funds are less likely to beat the market than small and new funds. So, there an opportunity for LP investors to increase returns by finding and de-risking new managers.

Here are three theories that attempt to explain the outperformance of first time funds. Take your pick:

- Smaller funds make more money because each investment gets more attention. They also have higher variance, with some upside on risk/return.

- New funds go into new markets with excess returns.

- The founders of new funds know they must close some good deals early. So, they save up some good deals and bring them over from their previous employment.

It’s possible that coop funds will get access to good deals, through their buy-side investors. Good investment deals don’t come from sell-side pitches. They come from buy-side investors who put in their own time and money to design deals that will make money.

Show Me the Money

Public markets value PE investment companies at about 6% of assets under management. A smaller and newer operating company might be worth less. However, a pioneering coop fund might be worth more, because it would be developing software, investor lists, and infrastructure for a new industry.

I’m going to imagine a scenario where a coop fund raises $1B for the fund, and ends up with $50M in operating company value (5%). This seems conservative. We’ll reserve half of the shares for operating company founders and infrastructure investors, and distribute half (worth $25M) to fund investors.

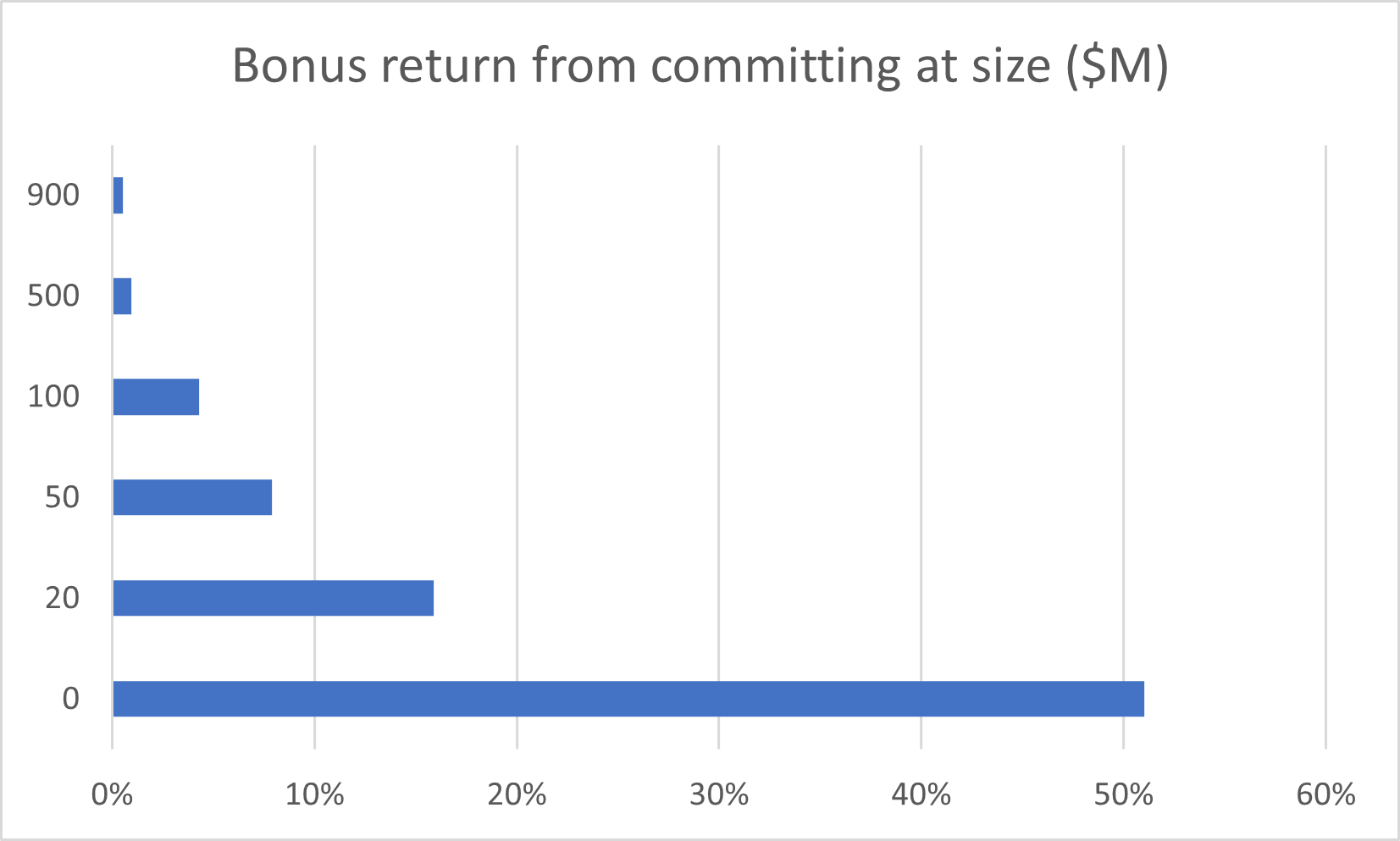

In this scenario, investors earn more shares if they invest earlier. If you invest when the fund has size S, you get twice as many operating shares compared to investing when the fund has size 2S.

The calculation of these share bonuses involves integrals and log functions. We will start with a base value, B, and each dollar of new investment earns shares proportional to 1/(B+S). This scenario sets B to $5M.

- The first $10M commitment earns 17% of the operating company, which ends up being worth $5,183,779, for a bonus return of 51%. Great ride! Real voting power!

- An investor that puts $10M after $100M has been committed earns about 1% of the operating company, for a bonus return of 4.29%. In today’s environment, that’s good.

- An investor that puts in $10M after $900M has been committed earns a bonus return of about 0.5%. The fund is pretty much at target, the other investors are helping with governance, and the bonus return is fast.

Money for Nothing

Investors will get equity value before they send any money for capital calls. Money for nothing! Infinite returns! This is not going to be a lot of money, but it is a meaningful booking in a business where returns typically take a long time to realize.

Advances for Digital Private Markets

This proposal for a Coop Fund is one of the things that we have been working on over at Unbundled Fund. We are taking a realistic look at the components of a “digital” private market.

- Designed and analyzed to increase returns for investors

- For qualified professionals

- With reliable automated reporting

- Using global sourcing and syndication networks

- Leading to an appropriate secondary market

Great stuff!